Dmitri Shostakovich was born in St. Petersburg in 1906. He was a child prodigy at the piano, had perfect pitch and a photographic memory. Among his teachers was the composer Alexander Glazunov and Shostakovich considered Mussorgsky to be one of the greatest Russian composers.

Shostakovich was incredibly prolific. He composed the music for some 40 movies, several ballets and operas, 15 string quartets, 15 symphonies, 2 violin concertos, 2 cello concertos, 2 piano concertos, and a lot more!

Stalin was responsible for the death of 30 million Russians. Shostakovich’s friends kept disappearing. His colleagues, patrons and members of his family were arrested and shot, including his brother-in-law, his mother-in-law and his uncle. In 1937 and 1938 1.5 million people were arrested and 668,000 were killed, averaging 880 executions a day.

Stalin wanted Soviet composers to write music that was joyful and optimistic. Shostakovich often did the opposite. He expressed the terror, fear, and frustration of living in Stalinist Russia. He said to his friend Isaac Glickman: “Even if they cut off both my hands and I have to hold my pen in my teeth I shall go on writing music.” His 4th symphony was prohibited from being performed, and its world premiere took place 25 years after it was written.

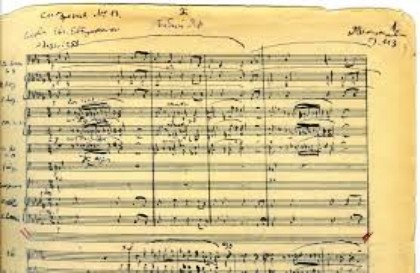

Stalin wanted triumphant music that would glorify himself and the Soviet Union, but Shostakovich outsmarted him. His 5th Symphony depicts the murder and horrific realities of the times. But in the finale, he composed music with trumpets and kettle drums in D major, the same key as Beethoven’s 9th Symphony, the Ode to Joy! Near the end of the finale, Shostakovich indicated a metronome number that called for this music to be performed at half the normal sounding speed.

He said: “The rejoicing is forced, created under threat. It’s as if someone were beating you with a stick, saying ‘Your business is rejoicing, your business is rejoicing’, and you rise up, shaky, and go marching off, muttering, ‘Our business is rejoicing.’ Stalin liked it because he thought Shostakovich was glorifying him, not realizing the composer’s true intent! The government dubbed the symphony “A constructive creative answer of a Soviet artist to well deserved criticism”. Stalin accepted it and never caught on to Shostakovich’s trick.

However in 1948 Stalin persecuted Shostakovich again. A formal decree was announced naming the three most prominent Russian composers of the day, Prokofiev, Shostakovich, and Khachaturian as enemies of the people for writing music that went against Soviet ideals. Shostakovich lost his teaching positions and his music was banned. He wrote: “I have very frequent headaches and am almost constantly nauseated.” He was denounced across the country, subjected to terrible ridicule in the press, and was even forced to slander himself at a public meeting. His speech was written for him by the government. He expected to be arrested and was contemplating suicide. Shostakovich kept a packed suitcase next to his door, expecting that at anytime he might be arrested by the KGB (the secret police). As these arrests often occurred in the middle of the night, Shostakovich sometimes slept in the stairwell of his apartment building because if the KGB did come for him, he didn’t want his wife and young children to be traumatized by watching them take him away. And when he left his home he began packing soap and a toothbrush, never knowing whether he would return.

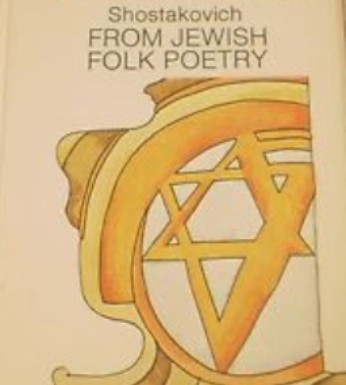

Shostakovich identified with Jews as the victims of thousands of years of injustice. He said “I often test a person by his attitude toward Jews. I broke with even good friends if I saw they had any anti-Semitic tendencies.”

In 1944 when Shostakovich learned about what was happening in German concentration camps he wrote klezmer-like music in the finale of his 2nd Trio for Piano, Violin and Cello.

Shostakovich said: “Jewish folk music has made a most powerful impression on me. I never tire of delighting in it. It can appear to be happy while it is tragic. It’s almost always laughter through tears. Jews became a symbol for me. I tried to convey that feeling in my music. It was a bad time for Jews then. In fact, it’s always a bad time for them.”

Shostakovich found a volume of Jewish Folk Poetry that was translated into Russian, and he set 11 of the poems to music for piano, soprano, mezzo soprano and tenor entitled From Jewish Folk Poetry.

To write music on Jewish themes was a provocative act, a direct critique of the regime’s anti-Semitism. It was composed in 1948, the same year Stalin began his murderous campaign against the country’s leading Jewish poets, actors, and writers. Shostakovich kept it hidden in a drawer for 7 years before it was performed in public.

In 1948 Stalin had thousands of Jews arrested or fired as a prelude to a massive deportation plan. Shostakovich’s 1st Violin Concerto, written at that time for David Oistrakh, a Ukrainian Jew from Odessa and one of the greatest violinists of the 20th century, was another composition that the government banned from being performed.

When Shostakovich was forced to join the communist party in 1960, he almost suffered a nervous breakdown, and purchased a large quantity of sleeping pills because he was thinking of suicide. He then composed his 8th String Quartet in 3 days as a requiem for himself. He wrote: “In composing it I shed as many tears as urine flows after half a dozen mugs of beer.”

In September of 1941, just outside of Kiev, Ukraine at a ravine called Babi Yar, the Nazis murdered 37,000 Jews in 48 hours, the single most horrific massacre of the Holocaust.

20 years later, the poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko was shown the area, and he was repulsed to discover that there was not even a memorial stone at the site. He immediately wrote the poem Babi Yar, which was published and became an instant sensation across Russia. Shostakovich read it and decided to set it to music. He then set 4 additional poems by Yevtushenko that described in graphic detail the conditions of living under the terror of Stalin. The result was his 13th Symphony, subtitled Babi Yar, written in 1962 for large symphony orchestra, a chorus of basses and baritones, and a bass soloist.

At a rehearsal the young bass soloist who had just graduated from the conservatory asked Shostakovich “Why are you writing about anti-Semitism when there isn’t any?” Shostakovich exploded. The rehearsal was ruined. He wouldn’t calm down. Shostakovich replied, almost shouting: “No there is, there is anti-Semitism in the Soviet Union. It is an outrageous thing and we must fight it. We must shout it from the rooftops.” The government tried to prevent the world premiere from taking place. The performance did take place on December 18, 1962, and the symphony was banned for the next 30 years. It took tremendous courage on Shostakovich’s part to write such a symphony; in fact when he returned home that night, he found KGB agents outside his apartment in case he tried to defect.

Shostakovich died in 1975 at age 69. He had several illnesses in his final years including heart disease and lung cancer, though he continued composing right to the end.