Louis Armstrong was the first African American to host a national radio show in 1937. He was the first jazz musician to appear on the cover of Time magazine in 1949, and the first African American to receive featured billing in a major Hollywood movie. In fact, he made more than 12 Hollywood films. The composer of over 50 songs, Armstrong was not only a musical genius; he was also a civil rights pioneer who beat all the odds, rising up from the lowest levels of poverty to become America’s ambassador of goodwill.

Born in 1901 in New Orleans, his part of town was the red light district of a black ghetto. Violence was so prevalent, it was called the “Battlefield”. It was a world of pimps, hustlers, prostitutes, saloons and gambling houses. His mother gave birth to him when she was just 15. She worked as a maid by day and sometimes moonlighted as a prostitute at night. Abandoned by his father in infancy, Louis only went as far as 5th grade because he had to work. He sold newspapers, picked through garbage for food, and for junk that could be resold, and he sold coal to prostitutes to keep their rooms warm. At 12, he was arrested for firing his stepfather’s pistol into the air on New Year’s Eve, and was placed in a reform school, the Colored Waif’s Home for Boys. He lived there for a year and a half in military style, learning discipline and distinguishing himself in the Waif’s Home band. Louis soon became successful singing in barbershop quartets on street corners and at playing the cornet.

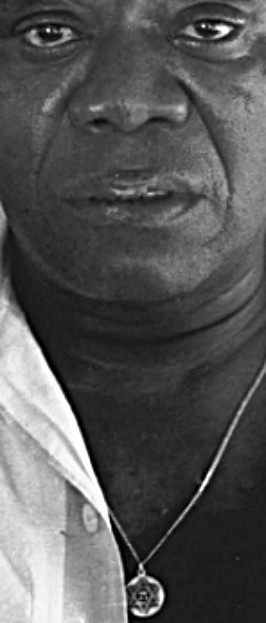

Near the end of his life, he wrote extensively about his relationship with the Karnovsky’s, a family of Lithuanian immigrants that treated him as a member of their family, gave him his first job, and lent him the money to buy his first cornet. He wrote: “We never forgotten each other. I got good on my cornet. Everywhere that I played and the Karnovsky’s could attend they would be there rooting for me as usual, always asking me if I needed anything. All that I needed was a little encouragement to bring it out of me and they did, thank God. The Jewish people sure did turn me out in many ways. They were so warm and made a little Negro boy such as me feel like a human being. If it wasn’t for the nice Jewish people we would have starved many times. I will love the Jewish people all of my life.” The Karnovsky’s included him in their Shabat dinners and throughout his life, he always kept matza in his kitchen. Armstrong told his manager that if he booked a tour to Israel to make sure that he’d perform there gratis. Armstrong wore a Star of David around his neck for the greater part of his life.

At age 21, Louis received a telegram from his mentor, Joe “King” Oliver, who had moved to Chicago, inviting Louis to join his band as 2nd cornet player. Armstrong: “The word had spread around Joe Oliver got a little second cornet player, and they’re making breaks together and doing a lot of things together. You’ve got to hear them. I was interested in Joe Oliver and I knew the way he played. I practically know everything he played. So I put notes to it. Surprised him. I would make duets to whatever he played. And all the musicians thought that was great! They tried it and everything, but they didn’t concentrate the way we did. They couldn’t do it unless they wrote it down. But we didn’t write anything — never did write it down.”

Armstrong’s reputation rapidly grew. In fact, his recordings from the 1920s and ’30s were so popular, that when he first appeared in Copenhagen, Denmark in 1933, there were over 10,000 fans waiting to greet him at the railroad station! His early recordings popularized scat singing, the vocalization of nonsense syllables in imitation of an instrument.

Wynton Marsalis: “He invented American singing. I mean all of the singers from Frank Sinatra, Bing Crosby, Mildred Bailey, Jon Henricks. You can go into any style, Sarah Vaughn, Billie Holiday. They all will say, ‘Pops.’ He was a man of great majesty. I just feel honored to speak about Louis Armstrong, and I just hope as many people as possible get hip to him. And it will enrich your life to check Pops out, because boy, it certainly enriched mine. I listen to all kinds of music, from Bach, Palestrina, Wagner, I don’t care. Pops was bad.”

Bing Crosby said: “I know of no man for whom I had more admiration and respect. He was a true genius but more.”

Tony Bennett: “It’s really America’s classical music. This becomes our tradition. The bottom line of any country in the world is: what did we contribute to the world? And we contributed Louis Armstrong.”

After performances, Armstrong always brought stacks of photos to give to his fans, who wanted to meet him and get his autograph. He was very happy to personally inscribe his photos to them, and he remained backstage for hours doing this until he had met with each person long after the rest of the band had gone back to the hotel.

Armstrong: “The main thing is to live for that audience, ’cause what you’re there for is to please the people the best way you can. Those few moments belong to them. I’m not lookin to be on no high pedestal. They get their soul lifted because they got the same soul I have the minute I hit a note.”

By the early ’30s, Armstrong had had run-ins with the police and was in a very difficult situation with his former managers and the mafia. He was also being hounded by his 1st ex-wife for money. In 1935 He approached Joe Glaser, a Jewish nightclub manager in Chicago that he had worked for in the past, and said to him: “I want you to be my manager. You get me the jobs. You collect the money. You hire the band members, pay them, discipline them, and if necessary, fire the band. You give my wife an allowance on schedule, you make and pay for all the travel and hotel arrangements on tour, and you pay my income tax. I want $1,000 every week free and clear and you take everything that’s left.” Armstrong and Glaser shook hands and for the next 35 years did business together without having a contract! Armstrong wrote: “I don’t know what any of the men get. I can’t concentrate, and play my heart out, and pay the musicians off. I don’t need contracts.” Eventually, they settled on a 50/50 split, and neither one of them ever complained about their financial agreement! Both men became multi-millionaires.

Armstrong purchased a house in the Corona section of Queens, New York in 1943. Years later his manager proposed that Louis buy a mansion on Long Island, saying that he could even have a swimming pool built in the shape of a trumpet, but Louis refused. He loved his house and was very happy in Corona. He repeatedly said that he had watched three generations of children grow up on his block. When he returned from his tours the kids on the block would enthusiastically help him into the house carrying his luggage. Louis loved to watch westerns on TV with them while his wife served everyone ice cream. He lived in this home until his death in 1971. He died in his sleep in this house. It is now a museum, and all the furniture and paintings are there, exactly the way he and his wife left them. Fans come from around the world to take the guided tours that are given every hour.

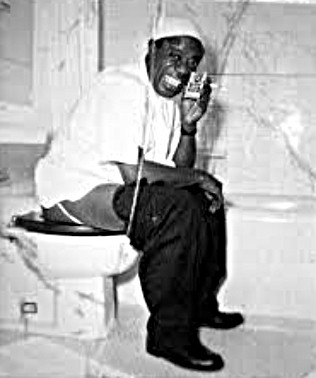

Armstrong loved to smoke marijuana on a daily basis. And as a boy, his mother instilled in him the practice of consuming herbs to clean out his intestines and colon. Years later when he discovered the herbal laxative Swiss Kris, he was overjoyed. Every night before going to bed he took a large dosage of Swiss Kriss. He loved to listen to music, a lot, and had loudspeakers built into the walls of every room, including the bathrooms! So in the morning, when the effects of the herbal laxative from the night before kicked in, he would enter the bathroom, smoking his marijuana, while listening to great music, and really enjoy himself!

Tony Bennett recalled: “We went to a big royal dinner with everybody there: Princess Alexandra, the Duke of Kent, and all the royalty with rubles and emeralds and diamonds. I couldn’t believe what I was witnessing. I was sitting next to Princess Alexandra and he was on the other side of Princess Alexandra, who was a beautiful lady. And he was talking to her and myself once in a while. But at the end of the meal when the dessert came, she turned around to me. She said: ‘Did you ever try this?’ And I looked at it and it was his commercial product that he always advertised, Swiss Kriss. And of course, it’s a laxative and a ferocious laxative. I was at a loss for words. I didn’t know what to say. And the Duke of Kent said: ‘What is it, my dear?’ So he starts handing it out to the royalty of England. He said: ‘Get it all out! It’s good for you. Get it all out!’ Well, when they read the instructions that it was a laxative, I never saw — it was like a barrel of white monkeys. I mean everybody just fell on the floor, pounding the floor. It was the funniest thing I’ve actually ever seen. It was funnier than any Laurel and Hardy scene.”

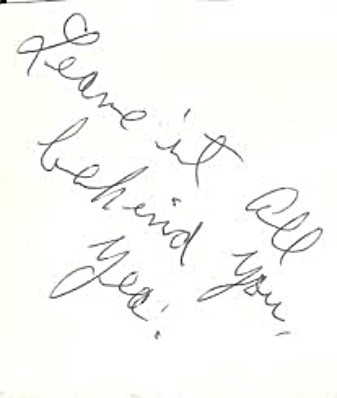

Armstrong even had a card made with a photo of himself sitting on the toilet, which he sent to his friends, and on the back, he wrote: “Leave it all behind you, yea!”

One of his bathrooms is covered with floor to ceiling mirrors, white marble, and gold plated fixtures. He really appreciated his bathroom especially since as a boy in New Orleans his dirt floor residence didn’t have a bathroom. He shared an outhouse with the neighbors on his block.

Louis said: “I never tried in no way to ever be real, real filthy rich like some people do and after they do, they die just the same. You got to live with that horn. I don’t want a million dollars. See what I mean? No medals. That’s my livin’ and my life. I love them notes. That’s why I try to make ’em right. I get out of that bed every day, see? I make a good salary and my horn still sounds good and I feel good. So I don’t think nobody in the world is richer than I am.”

Duke Ellington said: “If anyone was Mr. Jazz it was Louis Armstrong. He was the epitome of jazz and always will be.”

Wynton Marsalis: “Louis Armstrong invented a new style of playing. Louis Armstrong created the coherent solo. Louis Armstrong fused the sound of the blues with American popular song. Louis Armstrong extended the range of the trumpet. Louis Armstrong created the melodic and rhythmic vocabulary all of the big bands wrote music out of.”

Dizzy Gillespie: “Never before in the history of black music had one individual so completely dominated an art form as the master: Louis Daniel Armstrong.”

Armstrong was quite prolific. He wrote thousands of letters and liked to bring his typewriter along on tours. He is the author of not only one, but two autobiographies.

Armstrong purchased two tape recorders when they appeared on the market in the late 40s. He began traveling with them on tour so he could record his performances each night, and then afterward, at the hotel, listen to how he had played because he was always striving to improve. Behind his desk, in his home, he had installed into the wall state of the art sound equipment. It was here that he created tape recordings of thousands of hours of music from the radio and his extensive record collection.

Part of Armstrong’s style was influenced by Italian opera. In his childhood in New Orleans, he heard recordings of the popular opera singers of the day. And his favorite was Enrico Caruso. In his 1927 recording of ‘New Orleans Stomp’, he inserted part of the Quartet from Verdi’s ‘Rigoletto’! Louis believed that one should listen to all kinds of music. For example, he loved hearing Luisa Tetrazzini and John McCormack. According to Ricky Riccardi, biographer and curator of the Louis Armstrong Archives at Queens College in New York, Armstrong owned more recordings of opera and classical instrumental music than any other genre, including recordings of Toscanini, Beethoven, Verdi, and Wagner! Above his piano in the living room still hangs a drawing of Toscanini!

The Buddhist philosopher Daisaku Ikeda wrote: “The great task for all people is to learn how to resonate with the hearts of other people, and thus put a stop to the sanguinary scenes that blemish our world. If this is true, then I venture to say that music has been destined to attract our attention as one of the most effective ways to make us equal to this task.” Armstrong too was convinced of the very powerful influence of music. In 1959 he was performing at night in Victoria Hall in Geneva Switzerland. The same venue was being used that week in the daytime for a conference of foreign ministers from France, England, the Soviet Union, and the United States. Armstrong wrote: “Music has done a whole lot for friendships and everything. Just think if they sent this combo around to a big stadium where thousands of people could hear it — I think it would do a lot of good. If it’s left to people that’s peaceful with music, there wouldn’t be no wars. Wouldn’t be none. If I could get them cats to sit still and listen, well then, daddy, maybe I can relax them a little. Get them cats to relax and daddy, they’ll just relax this tension in the world.”

Armstrong performed in 15 African countries. In Zaire, he was carried on a throne! His appearance in Zaire interrupted a civil war because both sides wanted to listen to him perform. When he arrived in Ghana he was greeted by over 10,000 fans, including 13 brass bands! He and his own band took out their instruments and joined in.

Armstrong was repeatedly subjected to the humiliation of racism and segregation, especially when he performed in the south. He and his band members had to use service entrances; there were often no bathrooms for African Americans; they couldn’t get meals served nor hotel accommodations and often had to sleep on the bus. In Memphis in 1931, he and the band were jailed for sitting on their tour bus with a white person. For 10 years he boycotted his hometown of New Orleans because his band was racially integrated and was therefore not welcome there.

In February of 1957 during a performance before an integrated audience in Knoxville, dynamite was thrown at the auditorium. 7 months later Orval Faubus, the governor of Arkansas defied the Supreme Court and called in the National Guard with rifles and bayonets to prevent black children from entering Little Rock Central High School. Armstrong became enraged when he watched on TV the fearful expressions on the children’s faces, the vicious heckling of the white crowd, and the footage of a white man spitting in the face of a black girl.

The incident was an embarrassment to the United States. The cold war was escalating and Armstrong had just been asked by the U.S. State Dept. to embark on a goodwill tour of the Soviet Union.

He was interviewed about the upcoming tour.

Q: “What are you going to tell the Russians when they ask you about the Little Rock incident?”

Armstrong: “It all depends what time they send me over there. I don’t think they should send me now unless they straighten that mess down south. And for good, not just to blow over and cut it out I think because they’ve been ignoring the constitution, although they taught it in school, but when they go home their parents tell them different say you don’t have to abide by it because we’ve been getting away with it for a hundred years. So nobody tells on each other so don’t bother with it. But if they ask me what’s happening if I go now, I can’t tell a lie, that’s one thing. There’s no sense lying the way I feel about it.”

Armstrong canceled the tour, and when a reporter asked for his reaction, he said: “The way they’re treating my people in the south, the government can go to hell. It’s getting so bad, a colored man hasn’t got any country.” Armstrong called the governor a “no good motherfucker”, and called President Eisenhower “two-faced”, saying that he had “no guts” for not standing up to the governor.. No other jazz musician had the courage to speak out as strongly as Armstrong. His white road manager contradicted Armstrong’s statements. Arvell Shaw, Louis’s bass player for many years remembered the incident. “Cause he’s thinking about those big fees, you know. He said: ‘Louie Armstrong never said anything about that. He didn’t say anything like that.’ Louis said: ‘Yes I did. I meant it and I’ll stand by it till my dying day. All I ask is that they take those little kids into school. Why can’t they go to school?’”

Two weeks later Eisenhower sent 1,000 troops from the U.S. Army to enforce federal law and escort the students into the school.

Armstrong sent the president a telegram, which reads in part: “Mr. President. If and when you decide to take those little Negro children personally into central high school along with your marvelous troops please take me along.” After the incident, radio stations refused to play Armstrong’s recordings, fearing that he had become too controversial. Arvell Shaw: “What he did, what he played came from within. It came from his own heart, from his mind. It wasn’t anything contrived. It was him. It was Louis, what he was, the essence of his being. That’s the difference. He was a completely honest man musically, and in every other way that I knew about.”

Ossie Davis recalled a lunch break during the shooting of ‘A Man Called Adam’ in 1966. “Louie Armstrong. He was a dangerous man too. But it took me a long time to find it out. Most of the fellas I grew up with, myself included, we used to laugh at Louie Armstrong. We knew he could play the horn, but that didn’t save him from our malice and our ridicule. Everywhere we looked there had to be ole Louie. Sweat poppin, eyes buggin, mouth wide open, grinnin, oh my lord, from ear to ear. Oofta we called it. Moppin his brow, duckin his head, doin his thing to please the white folk, to make them happy. It made us look like fools. It wasn’t until 1966 when we were working together on a picture in New York with Sammy Davis Jr. and Cisely Tyson that I began to understand something about Louie. One day, we’d broken for lunch. And I decided to stay inside. It was quiet, so I thought that everybody had gone, and I went back on the set to lie down on the bed. And there was Louie by the door, sitting in a chair, staring up and out into space with the saddest, most heartbreaking expression I’ve ever seen on a man’s face. I just stared at him for a moment. And then when I tried to turn and sneak away, because it seemed like such a private moment, the noise snapped Louie out of it, and all of a sudden there was that professional grin again, mouth wide open. He whipped out his handkerchief, wiped his brow. “Hey Pops! Look like you cats tryin to starve ole Louie to death. Yeah!” I put on my face and grinned right back, but it wasn’t funny, not anymore. What I saw in that look shook me. There was my father, my uncle, myself, down through the generations doing exactly what Louie had had to do for the same reason, to survive. I never forgot that look. And I never laughed at Louie after that, for beneath that gravel voice and that shuffle, under all that mouth with more teeth than a piano had keys was a horn that could kill a man. That horn was where Louie kept his manhood hid all those years enough for him, enough for all of us. Louie man, I didn’t have sense enough to tell you this when I was a kid. I guess I didn’t even know it myself, but I love you, and I’m not the only one.”

Lester Bowie: “A lot of people put Louie down. They said that what he was doing was Toming. But the true revolutionary is one that’s not apparent. I mean the true revolutionary isn’t out waving a gun in the streets. It is never effective; the police just arrest him. But the police don’t ever know about the guy that smiles and drops a little poison in their coffee. Well, Louie was that sort of revolutionary, a true revolutionary. He revolutionized the aspect of music as an art form, as a musician being a cultural ambassador.”

Dizzy Gillespie wrote: “I began to realize what I considered Pop’s grinning in the face of racism as his absolute refusal to let anything, even anger about racism, steal the joy from his life and erase his fantastic smile. Coming from a younger generation, I misjudged him.”

Miles Davis said: “You can’t play anything on that horn that Louis hasn’t played. The great style and interpretation that Louis gave to us musically came from the heart. They call you a Tom but Louis fooled all of them and became an ambassador of goodwill.”

In 1929 Armstrong recorded the song ‘What did I do to be so black and blue’ from the Broadway show ‘Hot Chocolates’ that he performed in that same year. Some of the song’s lyrics are:

Even the mouse…ran from my house. They laugh at you…and all that you do. What did I do…to be so black and blue?

I’m white…inside…but, that don’t help my case. That’s life…can’t hide…what is in my face.

How would it end…ain’t got a friend. My only sin…is in my skin.

What did I do…to be so black and blue?

During the civil rights movement, he was widely criticized by the black community for not participating in the protest marches. In 1965, during the voter registration protest march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, the police had brutally attacked and beaten many of the 600 activists participating in the march. Armstrong defended his decision not to take part in the protest marches saying: “If I’d be out somewhere marching with a sign and some cat hits me in my chops, I’m finished. A trumpet man gets hit in the chops and he’s through… If my people don’t go along with me giving my dough instead of marching, well — every cat’s entitled to his own opinion. But that way I figure I can help out and still keep on working.” A reporter asked whether he would really be attacked, considering his stature and fame. Armstrong replied: “They would even beat Jesus if he was black and marched. How is it possible that human beings can still treat each other that way? Hitler is dead a long time — or is he?”

Armstrong was the first American entertainer to perform in East Berlin during the Cold War. He performed ‘Black and Blue’ there in 1965, just 2 weeks after the Selma incident. He may have been referring to his decision not to march in the streets when he changed the words from “I’m white inside” to “I’m right inside.” His biographer, Ricki Riccardi called this his protest song.

Armstrong never lost his humility. For example, at one point his manager sent him a limousine to ride in during one of his tours. He refused to ride in it, preferring instead to ride with his band on the bus. And at his neighborhood barbershop in Queens, his barber recalled that Louis always insisted on waiting his turn and never accepted the barber’s offers to take him ahead of the others.

Armstrong was incredibly generous. He kept two rolls of cash in his pockets. One for himself and the other, to give away. He gave away approximately $1,000 every week! And it wasn’t unusual for him to instruct his manager to buy new Cadillacs as gifts for family members and his girlfriends!

Arvell Shaw remembered one song that Louis Armstrong didn’t like at all at first. “We were playing a club in Chicago and our off day was Sunday. So we got a call from Joe Glaser, Louis’s agent. He said, ‘I want you to go on to New York on your off day to make a recording.’ So we flew into New York on Sunday, got to the studio, and they gave Louie the sheet music. And Louie looked at it and heard it down. He said: ‘You mean to tell me you called me out here to do this?’ He hated it, you know. But we did it; we made the record. Then we went back to Chicago to finish the engagement. Three or four months later we were doing one-nighters in Nebraska and Iowa, way out. And every night we’d hear from the audience ‘Hello, Dolly; Hello, Dolly.’ So the first couple nights Louie ignored it. And it got louder: ‘Hello, Dolly.’ So Louie looked at me, he said: ‘What the hell is ‘Hello, Dolly?’ I said: ‘Well you remember that date we did a few months ago in New York? One of the tunes was called ‘Hello, Dolly’. It’s from a Broadway show.’ We had to call and get the music and learn it and put it in the concert. And the first time we put it in the concert pandemonium broke out.” In 1964 Armstrong’s recording of ‘Hello Dolly’ soon eclipsed the Beatles as the number one hit on the Billboard Hot 100!

Armstrong had a terrible diet that included lots of fatty bacon, pork, a lot of salt, and he smoked unfiltered cigarettes. He suffered from heart disease and had several heart attacks. His last professional appearances were during a 2-week engagement at New York’s Waldorf Astoria Hotel just 3 ½ months before his death. He was very ill, and his doctor wanted him to cancel the contract, explaining that it was quite possible he could die right on stage, to which Armstrong replied:

“Doc, that’s alright. I don’t care. Doc, you don’t understand. My whole life, my whole soul, my whole spirit is to b-l-o-w that h-o-r-n.”

He played the 2-week engagement, despite being incredibly ill. Armstrong died in his sleep in his house in Queens, New York on July 6, 1971. He was 69.

In 1995 the U.S. Post Office issued a Louis Armstrong commemorative stamp. The 14,000-seat U.S. Open Tennis stadium in Queens, New York, is named the Louis Armstrong Stadium. The 32-acre Louis Armstrong Park in New Orleans is home to a 12-foot statue of the musician. And the Louis Armstrong New Orleans International Airport was named after him in 2001.

Watch video tease: https://youtu.be/7Q3ImfbPuOw

And for an amazing treasure trove of information and recordings to hear, this is the blog of Armstrong’s wonderful biographer, Ricky Riccardi: