Pau Casals was born in 1876 in Vendrell, Catalonia, near Barcelona, Spain. Pau means peace in Catalan. At 11 he first heard the cello, which he began to play and very quickly advanced in his cello studies. In his younger years Casals practiced 6–7 hours a day. His practice sessions were sometimes torturous. “It is discouraging to repeat a passage over and over and still not match the sound in your mind.” At age 12 he single-handedly revolutionized the standard technique of cello playing!

As a teenager, Pablo became terribly depressed. “How much ugliness there was that I saw! How much evil! How much pain! Injustice and violence revolted me. I could not understand why there was such evil in the world…I could no longer lose myself in my music…Music must serve a purpose….A musician is also a human, and more important than his music is his attitude toward life…What brought me out of the abyss…was the hope in me that would not be destroyed.

“If there is in man infinite capacity for good, there is also infinite capacity for evil. Every one of us has within himself the possibilities of both…My mother used to say ‘Every man has good and bad within him. He must make his choice. You must hear the good in you and obey it.’”

Casals’s hectic international touring schedule averaged 250 concerts per year. In 1904 performed at the White House for President Teddy Roosevelt and more than a half century later, for President Kennedy. He was the highest paid instrumentalist of the day, and when Pablo’s press reviews became filled with extravagant praise, his mother taught him the importance of humility.

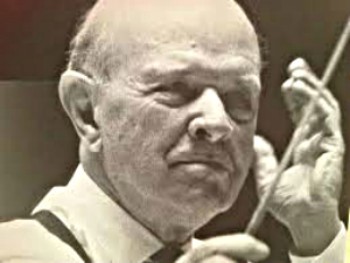

In 1919 Casals decided to establish a first rate symphony orchestra, which he conducted, the Orchestra Pau Casals in Barcelona, the capital of Catalonia. He couldn’t secure funding so he hand picked 88 musicians, and paid them double the low union rate. Each year he personally made up the deficit, and it took 7 years before the venture became self-sustaining.

He also created the Workingmen’s Concert Association, which offered symphony concerts, a music magazine, music library, music school, choruses and its own amateur orchestra, all for $1 per year. The membership eventually grew to more than 300,000. Casals’s efforts to bring great music to the masses made him a national hero, and the orchestra came to be thought of as a national treasure. He called this period “the most fruitful phase of my life.” The orchestra gave 370 concerts over a 17-year period and invited famous guest conductors, composers and soloists to perform with it until the Spanish Civil War began in 1936.

“First and foremost I am a Catalan. Catalonia is the land of my birth, and I love her as a mother. As early as the 11th century, Catalonia summoned a convocation that called for the abolishment of war in the world.”

Pablo remembered when his brother Enrique was 19 and called to serve in the Spanish army. His mother said to Enrique ‘My son, you do not have to kill anybody, and nobody has to kill you. You were not born to kill or be killed. Go away…leave the country.’ Enrique fled to Argentina.

Casals wrote: “As I toured foreign cities, I would read in the newspapers about the battles ravaging my land, the burning towns, the hungry children in cities under siege. The only weapons I have ever had are my cello and my conductor’s baton. And during the civil war I used them as best as I could to support the cause of freedom and democracy. While I was playing, I knew the bombs were falling. I could not sleep at night. After concerts I would walk the streets, alone in torment…

“I shut myself in a room with all the blinds drawn and sat staring into the dark. I remained in that room for days, unable to move. I was perhaps near to madness or to death. I did not really want to live.”

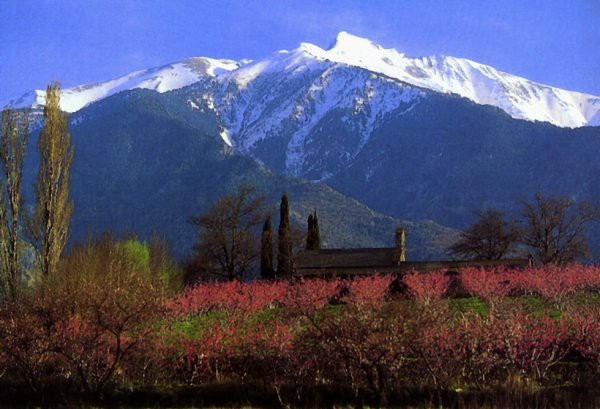

When one of Franco’s aides declared that he would like to cut off both of Casals’s arms at the elbow, it became obvious that he had to leave the country and in 1939 he moved across the Spanish border to Prades in the south of France. It was a small town of about 4,000 people. He stopped playing in public and lived there in exile for 17 years. He vowed not to return to Spain until democracy was restored.

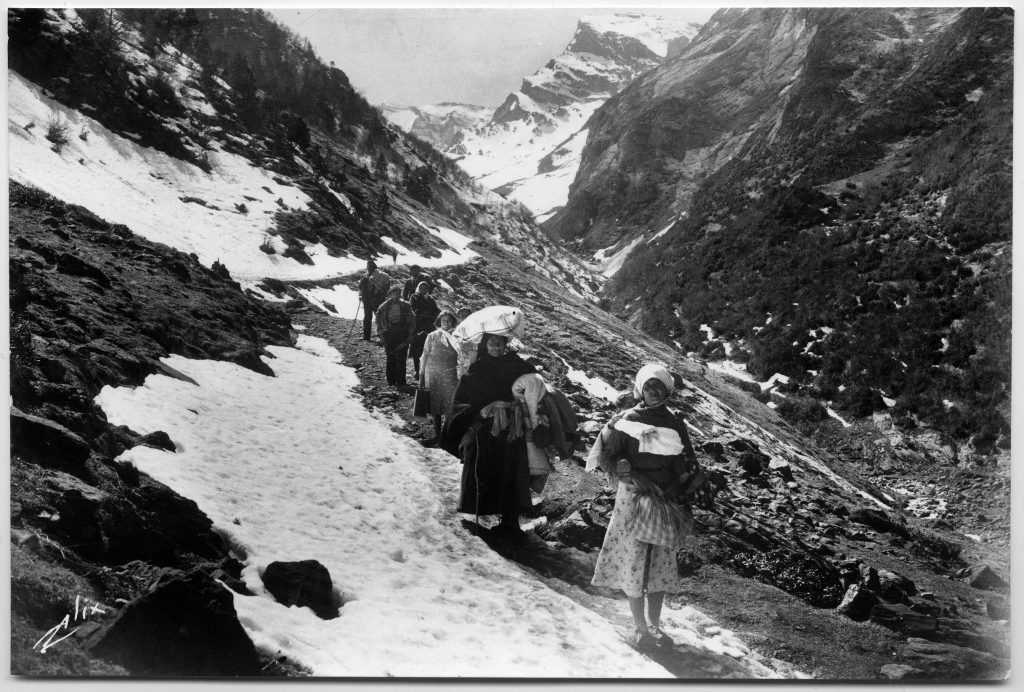

More than half a million refugees made their way across the Pyrenees into France in the dead of winter: men, women and children. Many of the sick and aged died in that procession of sorrow. They lived in concentration camps, which Casals visited. “The scenes I visited might have been from Dante’s Inferno. Tens of thousands herded together like animals. There were no sanitation facilities, medical care, little water, and barely enough food to keep from starvation. More than 100,000 refugees had been massed in open areas along the seashore. In the winter they had been provided with no shelter whatsoever, many had burrowed holes in the wet sand. The local hospitals overflowed with the sick and dying. When I saw the frightful conditions in those camps, I knew I had but one duty.”

Casals then spent years writing thousands of letters, for several hours each day asking for funds to assist the 600,000 refugees who were suffering under the Spanish dictator Franco. The world’s greatest cellist, a personal friend of kings and queens of Europe gave up his amazing career to help his compatriots.

The Buddhist philosopher, Daisaku Ikeda, in his novel, The New Human Revolution, volume 5, quoted Casals: “Politics do not belong to an artist but, to my mind, he is under an obligation to take sides, whatever sacrifice it means, if human dignity becomes involved.”

Ikeda wrote: “With the outbreak of World War II, Casals continued his unbending opposition to Franco’s government and the German and Italian fascists who supported it. The Nazis alternately threatened and tried to appease him.”

After World War II, Casals was surprised and saddened to learn that the allies, having deposed Hitler and Mussolini, chose to leave Franco in power. The United States government provided Franco with hundreds of millions of dollars in economic aid in return for permission to place its military bases in Spain. Casals refused to perform in any country that recognized Franco.

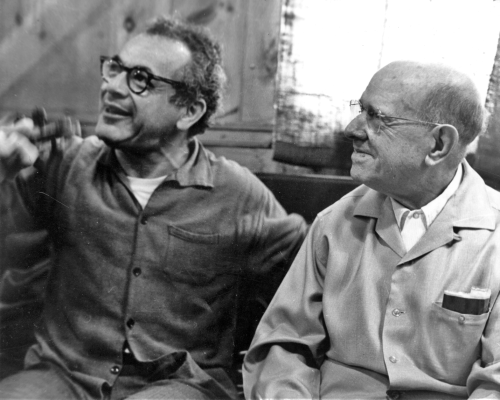

When the violinist, Alexander Schneider couldn’t convince Casals to break his musical silence, he proposed that an international Bach Festival be held in Prades to commemorate the 200th anniversary of the composer’s death in 1950. Casals agreed to participate on condition that all proceeds were to go to a refugee hospital in nearby Perpignan. The annual Prades festival is sill in existence today.

He made an impact on the Puerto Rican music scene, by founding the Casals Festival there in 1955, the Puerto Rico Symphony Orchestra in 1958, and the Conservatory of Music of Puerto Rico in 1959.

In 1957, at age 80, Casals married 20-year-old Marta Montañez y Martinez. He dismissed concerns that marriage to someone 60 years his junior might be hazardous by saying, “I look at it this way: if she dies, she dies!” Pau and Marta made their permanent residence in Puerto Rico until his death.

Daisaku Ikeda wrote about the message Casals wrote in 1958 when he was invited to perform at the United Nations. In his message, a prayer for peace, he “called for the eradication of all nuclear weapons and expressed a fervent hope for peace. In it he also spoke of the role of music and made the following proposal: ‘I make a special appeal to my fellow musicians everywhere, asking each one to put the purity of his art at the service of mankind in bringing about fraternal and enlightened relationships between men the world over.’

‘The Ode to Joy of Beethoven’s 9th Symphony has become a symbol of love. And I propose that every town which has an orchestra and chorus should perform it on the same day, and have it transmitted by radio to all corners of the world; and to perform it as another prayer through music for the Peace that we all desire and wait for.’ Through a magnificent chorus of Beethoven’s Ode to Joy, Casals sought to unite hearts all the world over who longed for peace.” Ikeda compared Casals to Picasso: “Both possessed an invincible spirit to resist evil and fight for peace and humanism. Both were committed to justice.”

Casals wrote: “It is not the peoples of the world but artificial barriers imposed by their governments that hold them apart.

“I am a man first, an artist second. As a man, my first obligation is to the welfare of my fellow men. I will endeavor to meet this obligation through music — the means god has given me — since it transcends language, politics and national boundaries. My contribution to world peace may be small. But at least I will have given all I can to an ideal I hold sacred.”

“All my life, music had been my only weapon…The artist has a particular responsibility, because he has been grated special sensitivities and perceptions, and because his voice may be heard when other voices are not.”

In his 90s Casals wrote: “Yes, at my age I have much to be thankful for. I have my beloved Martita, my friends and the joy of my work. Yet I cannot say my heart is tranquil. How can one be at peace when there is such turmoil and anguish in the world? Who can rest when the very existence of mankind is imperiled?”

When Casals, then 93, was asked why he continued to practice the cello three hours a day, Casals replied, “I’m beginning to notice some improvement.”

Casals died in Puerto Rico in 1973 just weeks before what world have been his 97th birthday. Franco died one year after Casals.

The Casals Festival in Puerto Rico continues to this day. Casals was awarded the U.S. Presidential Medal of Freedom, the United Nations Peace Medal, and was posthumously awarded a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award. The International Pau Casals Cello Competition is held in Germany every four years, and is supported by the Pau Casals Foundation. Schools in Chicago and New York City bear his name, as does part of a highway in Catalonia, as do concert halls in San Juan and Tokyo.

For more, see my blog: https://CesareCivetta.com/blog

Here is a phenomenally beautiful Casals video!