“Mother Teresa, How Can I Help You?”

Two months before his death, despite his debilitating illness, 82-year old Robert Shaw traveled at his own expense from Atlanta to Newton, Kansas to conduct a Sing-Along to raise funds and awareness for the prison choir of his longtime friend Elvera Voth. It was based on their strong beliefs that choral singing could transform lives and prompt social change by healing and empowering the disenfranchised. The event launched the non-profit organization, Arts in Prison, and inspired other prison-based choral and arts programs that continue to develop long past Shaw’s death.

Voth created a men’s prison choir, The East Hill Singers in the fall of 1995 to help rehabilitate inmates. At the first rehearsal approximately thirty inmates appeared in response to a poster that announced the formation of a singing group. Most of them thought they were joining a rap group. Accordingly, half of these men left during the rehearsal break.

For their first concert Voth invited men from the Rainbow Mennonite Church and the Lyric Opera of Kansas City to sing with the prisoners. Voth said, “In this chorus we have African-Americans, two American Indians, a Hispanic, old white guys, CEOs, doctors, opera singers, truck drivers, you name it. You can’t see another picture like that anywhere. Working in the prison has prompted me to question the meaning of loving my neighbor, of being part of a faith community whose highest calling is to minister to the disenfranchised, the forgotten, the undervalued. I don’t know how I could be so lucky. I’m now seventy-five years old, and I found the most interesting work of my life. You see the light in these guys’ eyes, and you remember what it’s all about.”

A former inmate singer shared how singing in the choir helped bridge racial gaps inherent in prison life. “It’s helping me as a person. I’m singing with a bunch of different guys. When I’m singing around these fellows, I don’t look at race. We’re one.” A local Mennonite pastor commented: “Here were men singing powerfully about spiritual realities who, regardless of their failures, were undeniably human along with the rest of us.”

In the 1980s in Georgia, Shaw had performed free parks concerts and free concerts for senior citizens, the handicapped, prison inmates and hospital patients. And he knew first hand the healing effects of choral singing: “I worked with choirs immediately following World War II including men who had flown fifty missions over Europe or fifty missions over Tokyo. There were scores and scores who said ‘this music has saved my life’ and found their way back to sanity and for a while they could forget their killing.”

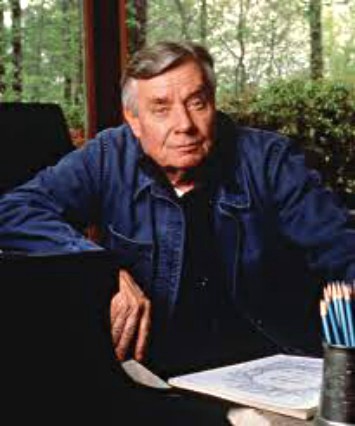

Robert Shaw served as artistic director of the Alaska Festival of Music from its beginning in 1956 through 1973. Voth moved to Alaska in 1962 and until 1973 she prepared choruses for Shaw. “Preparing many of the choral masterpieces for Mr. Shaw was the great privilege of my life. He is the hero of my life. He is a meticulous musician and certainly, to my mind both the most profound human being I have met in my lifetime and the wittiest. Robert Shaw, to my mind, is a great humanitarian first, and the world’s great choral conductor second.”

After attending an East Hill Singers performance in 1997, a friend of Voth sent Shaw a copy of the program with a letter in which she described the inmate narrations and the interaction between inmates and their families. “It was quite moving. All solos were sung by inmates. After the concert the inmates’ families came up to greet them and I can’t even describe that. Then we all had potluck and the inmates had a wonderful dinner with their families — kids, grandparents, girlfriends and various kith and kin.” Shortly after receiving the letter Shaw met another friend of Voth’s and with a big grin said, “Have you heard what that dear woman is doing?” He was clearly very elated about Voth’s work with inmates.

Shaw and Voth had not talked for approximately twenty-five years when Shaw telephoned Voth, who was astonished and pleased. Shaw told Elvera that he heard she was leading a prison choir. He said, “Is that true?” She replied, “Yes indeed.” There was a long pause, and then Shaw responded, “Well, Mother Theresa, how can I help you?” Shaw wanted to help because he viewed arts experiences as a key to sustaining humanity and crucial to human life: “The Arts and human creativity are not simply skills; their concern is the intellectual, ethical, and spiritual maturity of human life. The Arts are custodians of those values, which most worthily define humanity and may prove to be the only workable Program of Conservation for the human race on the planet.”

Shaw thought getting people involved in arts experiences, particularly musical performances, changed lives. He believed the arts were far more important than institutionalized religion: “Art has instituted no crusades, has burned neither witches nor books or started wars — and religion has.” He believed the Arts in Prison program could help with inmate rehabilitation by offering a healing experience for the incarcerated.

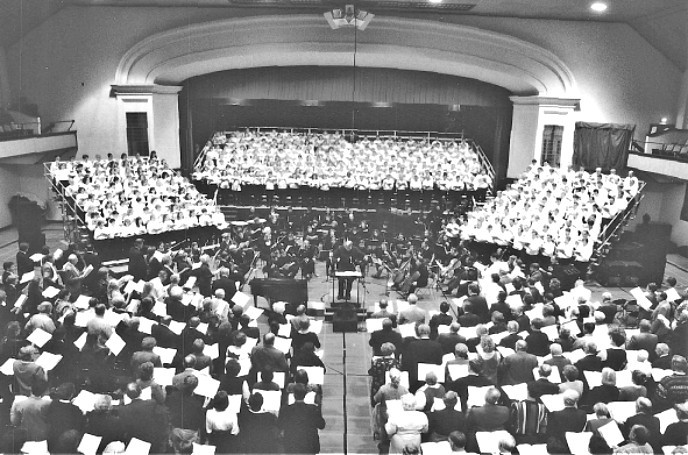

Prior to the Sing-Along the conductor had cancelled engagements with some of the nation’s leading orchestras due to his various terminal illnesses. But to Shaw this event was more important. Planners for the event were concerned whether Shaw’s health would allow him to travel to Newton, Kansas. They even considered purchasing cancellation insurance. Voth had written to Shaw’s assistant, Nola Frink: “If you Atlanta folks need medical assistance, my niece is the emergency room supervisor at the Newton Medical Center and will be on stand-by for your comfort.” He donated not only his time, but also his and his staff’s travel expenses. 1,275 people attended the event, which raised over $25,000.

With a shared vision of how arts can help society and the belief that group singing could contribute to healing and human transformation, Voth and Shaw tapped a vast reservoir of goodwill and concern for social justice that resulted in a powerful, grass-roots movement toward arts-based rehabilitation and corrections education in Kansas. Instrumentalists from six Kansas orchestras performed in the fifty member orchestra. And singers from 15 choruses swelled the size of the Sing-Along chorus to 450.

One inmate singer, Frank Dominguez developed hope, inspiration, and confidence. “Six months ago I was 34036 singing in this Lansing choir. And today I am Frank Dominguez singing with some of the finest voices around accompanied by my wife and my five children. What better way to help men reenter society rehabilitated then to allow them to participate in a program that aids in the building of high self esteem, confidence and a hope that may carry men through the rest of their lives as productive citizens in our society.”

Three professors decided to begin their own arts in prison projects. John McCabe-Juhnke took a sabbatical leave begin a drama program, driving three hours from Newton, Kansas to Lansing each way to lead his class in vocal exercises, personal reflections, and dramatic analyses of performance texts. Raylene Hinz-Penner began teaching poetry and creative writing to inmates and went on to teach five courses. Marles Preheim began a prison choir in the maximum security unit of the Hutchinson Correctional Facility. Within 9 years over three hundred inmates had participated in Voth’s East Hill Singers and over forty-five people had volunteered to teach arts classes.

Arts in Prison, Inc. added classes in visual arts, horticulture therapy, memoir writing, photography, creative writing, public speaking, guitar, poetry, yoga, African American history, film appreciation, clay, and drama. Choirs were established in the medium and maximum units at the Lansing and Osawatomie, Kansas Correctional Facilities.

Another inmate said: “Can you imagine what a standing ovation feels like after being told all your life that you are worthless?”

An East Hill inmate commented: “I never thought I would miss anything about prison life, but I will miss this chorus.”

A former inmate singer wrote: “I absolutely hate the behavior that resulted in my incarceration but I have stopped hating myself. It is programs like Arts in Prison that can help me in this process of believing in myself.”

You may view the entire event here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SoLzzeZik_0

Here is my detailed article about Shaw’s life and music:

https://cesarecivetta.com/the-legendary-maestro-robert-shaw/

This story was adapted from Mary L. Cohen’s article in the International Journal of Research in Choral Singing 2008.