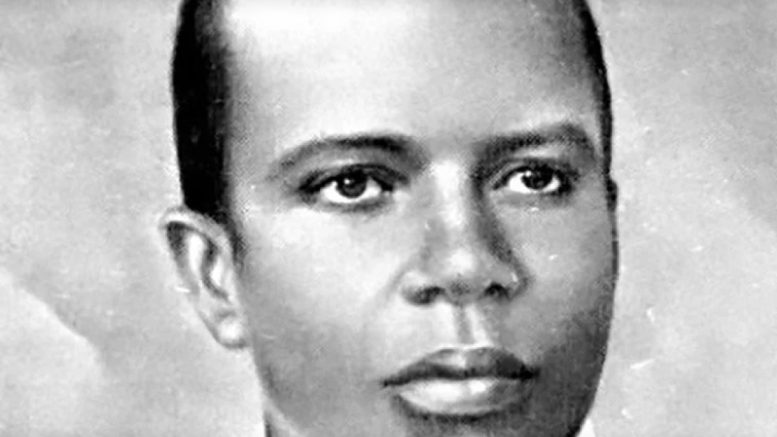

Scott Joplin was born in Northeast Texas in 1868 and grew up in Texarkana. His father an ex-slave worked as a laborer for the railroad and played violin. His mother was a maid, played the banjo and sang.

After the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863, African Americans were blamed for what their former slave owners lost economically. Therefore there was tremendous opposition to schools for African Americans. The few that existed were frequently attacked and burned. Teachers were whipped and beaten. It was considered the lowest position for a white person to be a teacher of Blacks. However, the Joplin children received private tutoring, paid for with food.

By age 7 Scott Joplin became proficient on the banjo and began accompanying his mother to the home of a white family, where she did domestic work, and where he was allowed to play their piano. Scott was a child prodigy. He had perfect pitch and his talent was noticed by some of the local music teachers, who gave him lessons for little or no pay.

His parents didn’t get along, and his father left the family when Scott was 12. As a boy, he spent the money he earned doing errands and odd jobs on popular sheet music. Joplin kept to himself and practiced. A family friend recalled: “Scott was earnest. When a bunch of boys got together one night and asked Scott to go with them, he said ‘No sir. I won’t have anything to do with such foolishness. I’m going to make a man out of myself.'”

He soon attracted the attention of Julius Weiss, a German Jewish immigrant who had been hired to tutor the children of a wealthy landowner. Weiss taught Joplin for free from age 11 to age 16. He tutored him in folk music, sight-reading, harmony, composition and the music of classical composers. He also helped Joplin’s mother buy a used piano for the boy to practice on at home. Joplin never forgot him, and later in life, sent Prof. Weiss money when he became old and sick until his teacher’s death.

Joplin played at church gatherings, taught guitar and mandolin, and at 16 formed a vocal quartet. He was a quiet, introverted person, yet he had a magnetic personality that attracted people to him. One of his friends recalled “Scott worked on his music all the time. He was a musical genius. He did not have to play anyone else’s music. He made up his own, and it was beautiful. He just got his music out of the air.”

Around age 20 he quit his job with the railroad, where he had been working as a laborer and became a traveling musician. He found steady employment in the brothels of the red light districts throughout the mid-south. In 1890 he moved to St. Louis, then known as “The Gateway to the West”. It was filled with saloons, gambling houses and bordellos, where musicians were in constant demand.

In 1893 he visited the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, a huge world’s fair, where he formed his 1st band, playing cornet, and piano, and made orchestrations for the band.

Ragtime music originally derived from spirituals and minstrel songs. By 1893 people wanted to break free from the restraints of traditional, Victorian culture. It was a racy alternative to the stuffy, respectable Victorian parlor music. Instead of Victorian genteel self control, ragtime’s rhythmic exuberance created an irresistible urge to dance. Its syncopated rhythm was an exciting departure from the usual order and regularity of waltzes, marches, hymns and dreamy ballads. But its popularity was controversial. At first Ragtime was not considered suitable for polite society. It was associated with lowlifes, saloons and bordellos. It was called “a disease, an epidemic, a rapidly increasing mania, and the source of physical and mental disturbances such as a frenzied mind, and abnormal heart action!” The criticisms were due to the vulgar lyrics of the songs, which Joplin deplored. Most of his rags are purely instrumental, without words. In order to promote Joplin’s music to respectable middle class families, his publisher advertised Joplin’s music as “classic rags…that have lifted Ragtime from its low estate and lined it up with Beethoven and Bach.”

In the 1890s piano manufacturers began making inexpensive pianos. By the end of the century there were 400 companies in the U.S. manufacturing 150,000 pianos a year, and many middle class families purchased pianos for their homes, which created the demand for ragtime sheet music.

In 1894 Joplin moved to Sedalia, Missouri, where he played 2nd cornet in the Queen City Concert Band, taught piano, sang in choirs, and worked as a piano accompanist. He composed Victorian songs, piano pieces, marches and waltzes. He performed at Black clubs and sang and conducted a male vocal octet called the Texas Medley Quartet with which he toured for 3 years. He also enrolled at the George R. Smith College for Negroes in the mid 1880s where he studied advanced harmony, theory and composition. Joplin’s colleagues recalled that he was always ready to help a fellow composer and never uttered a word of jealousy or condemnation.

It was in Sedalia that Joplin’s dramatic rise to fame occurred and he became known as the King of Ragtime. In 1899 he met John Stark, a local music storeowner and publisher. After hearing Joplin play his Maple Leaf Rag at the Maple Leaf Club, Stark decided to publish it and sold it for 50 cents per copy. He paid Joplin no money up front and only a royalty of 1 cent per copy sold. Thus began one of the legendary relationships in the history of American music based on mutual respect between a white businessman and a black composer. The Maple Leaf Rag only sold 400 copies the 1st year. Commenting on the fact that his music was not appreciated, Joplin said: “Maybe 50 years after I am dead it will be.”

Not long after the publication of the Maple Leaf Rag, Joplin composed The Ragtime Dance, a dramatic Ragtime folk ballet of 10 pieces with a vocal introduction and narration. He established the Scott Joplin Drama Company, and rented the Woods Opera House to put on 1 performance. Scott played the piano and conducted the orchestra. His publisher, John Stark was there, but the sales of the Maple Leaf Rag hadn’t begun to take off yet and Stark wouldn’t publish the ballet. Joplin was disappointed and it became a source of tension in their relationship. Three years later Joplin again produced a private performance of the Ragtime Dance, and this time Stark published it, but it didn’t sell well.

Also in 1899 Scott began a common law marriage with Belle Jones and they soon moved to a house in St. Louis where he composed and was a respected teacher. To supplement their income, Belle rented out several of the rooms transforming it into a boarding house. Their relationship was difficult, one reason being that Belle had no interest in music. They had a baby daughter, who died only a few months after birth. They soon separated, and a few years later Belle died.

In the fall of 1903 Joplin established the Scott Joplin Ragtime Opera Company, with which he produced his first opera: A Guest of Honor, and took it on tour. During the tour, the box office proceeds were stolen and the company was forced to abandon the remainder of the tour. The opera was never published and the music was lost. It has never been found. He returned to St. Louis after the tour, and then moved back to Sedalia in 1904. That year Scott married Freddie Alexander. She caught a cold that progressed into pneumonia and died at the age of 20, just 10 weeks after their wedding. Following her funeral, Scott left Sedalia and never returned.

1905 was a very non-productive period for Joplin.

Though Joplin’s ballet and opera didn’t spark any interest, his shorter compositions did. The Ragtime waltzes, 2 steps, and Slow Drags were very popular. By 1900 Ragtime was becoming a national craze. Sales of the music of the Maple Leaf Rag exploded! It has been played and recorded more than any other Ragtime piece.

His rags are very difficult to play. Therefore the public demanded a simpler form of ragtime music. In response, composers came up with a less complicated and more commercial style. Talented pianists began to play the rags faster and faster, showing off their virtuoso techniques and delighting and exciting the listeners. New York was a large, busy city, where faster and more nervous speeds of musical performance became the norm. The resulting tinny sound is where the name Tin Pan Alley came from. It was the genre of these New York City ragtime musicians. Tin Pan Alley was characterized by an underground, bohemian lifestyle: fast paced and lots of alcohol and drugs. Deaths from drug overdose and syphilis were common.

Joplin’s music was meant as a serious genre, not the music of a carnival atmosphere. Therefore his performances were less flashy than those of the virtuoso pianists and he often included these instructions on page 1 of his compositions: “Do not play this piece fast. It is never right to play Ragtime fast.” In 1908 he wrote and published an instructional manual consisting of exercises in the correct way to play Ragtime. It’s called School of Ragtime–6 Exercises for Piano.

In 1909 Joplin met and married Lottie Stokes. They moved into a house in New York City on W. 47th St., which Lottie ran as a theatrical boarding house, and where Scott gave violin and piano lessons. After a few years they moved to W.138th St. in Harlem. They later moved to W. 131st St. where Lottie rented out rooms to boarders and prostitutes.

He gradually performed less frequently, and devoted his time to composing and teaching. Sadly, some of Scott’s friends began deserting him and he was unable to penetrate the circle of black entertainers in Harlem. Amazingly, as Ragtime became the nations favorite music, The King of Ragtime got lost in the shuffle. This period also marked the development of the mechanical player piano—the pianola. These pianos used a paper roll, on which pianists made recordings, which then reproduced their performances on player pianos in homes. This resulted in fewer people purchasing the difficult sheet music of Joplin’s compositions.

His 2nd opera, Treemonisha, is a folk opera that takes place on a plantation in Arkansas in 1884. A married couple desires to have a child whom they would educate to grow up and teach their people to discard their beliefs in superstition. Their desire comes to fruition and they name their daughter Treemonisha. The opera deals with the birth and rise of a female black leader who leads her people out of ignorance and superstition, teaching the concepts of self-determination and self-government. Joplin worked on Treemonisha for 15 years, creating a thoroughly American opera. He was an optimist with a mission.

In 1911 Joplin tried unsuccessfully to find a publisher for Treemonisha. He therefore published it himself and then orchestrated it. It consists of 27 musical numbers. After searching for two years for a backer to produce the opera, the manager of the Lafayette Theatre in Harlem decided to stage it. However, the theatre then changed management, and the new manager decided not to produce it. For 2 more years Scott tried to interest backers. Finally, in 1915 he rented the Lincoln Theatre in Harlem and put on a concert version performance for an invited audience with himself at the piano, with the aim of attracting financial backers. The performance was a failure. No one was interested. The finale: Marching Onward implies that education, hard work, and morality will translate into progress for Americans. Its fundamental message was that education was essential for freedom. However, NewYork’s African American cultural leaders couldn’t identify with its message because they had had excellent formal education; they were not from the South, and knew very little about the oppressive plantation life. Scott was heart broken, and plunged into despair, suffering a breakdown. He was bankrupt, discouraged and worn out. For several weeks he was inconsolable.

His wife stated after his death: “He was a great man, a great man! He wanted to be a real leader. He wanted to free his people from poverty and ignorance, and superstition, just like the heroine of his opera Treemonisha. That’s why he was so ambitious; that’s why he tackled major projects. In fact, that’s why he was so far ahead of his time…”

At the end of his life Joplin was working on his 1st Symphony. But he began suffering from the effects of syphilis. Sometimes, when he tried to compose, his mind went blank. He would sit at the piano and not be able to remember his own music. A few months before his death he burned most of the manuscripts of his unfinished compositions. He experienced deep depressions, lost his physical coordination, and eventually lost his sanity. In 1917 he was taken to the Manhattan State Hospital for mental illness on Ward’s Island where he died two months later at the young age of 49. He was buried in a pauper’s grave in Queens, New York that remained unmarked for 57 years.

Then in 1970 Knocky Parker recorded a 2 record set of Joplin’s music for Audiophile Records. That same year Joshua Rifkin recorded an album of Joplin’s piano rags for the Nonesuch classical label. It sold 100,000 copies in its 1st year and became Nonesuch’s 1st million-selling record. Scott Joplin was inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame. In 1971 the New York Public Library published 2 volumes of Joplin’s music and excerpts from Treemonisha were performed at the Lincoln Center Library with piano accompaniment. In 1972 Robert Shaw conducted the world premiere of Treemonisha with the Atlanta Symphony and singers from Morehouse College. It was 61 years since Joplin had published it. In 1973 Gunther Schuller arranged and conducted an album of Joplin’s rags with the New England Ragtime Ensemble, which won a Grammy award and became Billboard Magazine’s Top Classical Album of 1974.

That year London’s Royal Ballet produced a ballet of Joplin’s music called Elite Syncopations and the Los Angeles Ballet produced a ballet of Joplin’s rags entitled Red Back Book. ‘The Sting’ starring Robert Redford and Paul Newman won the Oscar for Best Picture in 1974. Marvin Hamlisch adopted Joplin’s music for its sound track, for which he won an academy award. In 1975 Treemonisha was staged by the Houston Grand Opera, and after going on tour, ran for 8 weeks at the Palace Theatre on Broadway. Soprano Kathleen Battle sang the title role and an original Broadway cast recording was produced. In 1976 Joplin was awarded a special Pulitzer Prize.

In 1983 Joplin received a star on the St. Louis Walk of Fame and his St. Louis home, is now a National Historic Landmark.

That year the U.S. Postal Service issued its Scott Joplin stamp.