Puccini was born in Lucca, Italy in 1858. He came from a long line of composers dating back to the 18th century. Scenes de la vie de Bohème (Scenes from Bohemian life) was written by French writer Henry Murger when he was 25, and was published as a series of short stories in installments between 1845-1848. It depicts the world of young artists in Paris around 1830. Much of La Bohème was composed when Puccini was 37, and is based on incidents in his own life.

Puccini was almost exclusively a composer of operas. He wrote: “If only I could be a purely symphonic writer! Almighty God touched me with his little finger and said: ‘Write for the theatre, and only for the theatre.‘ And I have obeyed the supreme command.”

Puccini had to have the librettos (texts) to his operas finalized before he would compose the music. He was fanatically concerned with the words. Before he could set words to music, it was essential that the words would fire his spirit as if they were his own creation. There were months and years of attempts to find a story that he wanted to make into an opera which frequently resulted in nothing. His misery increased as time passed while he composed nothing. There were projects which sprang up, matured, and were suddenly abandoned. “If I touch the piano my hands get covered with dust. Music? Useless, if I have no libretto. I want a libretto which can move the world!”

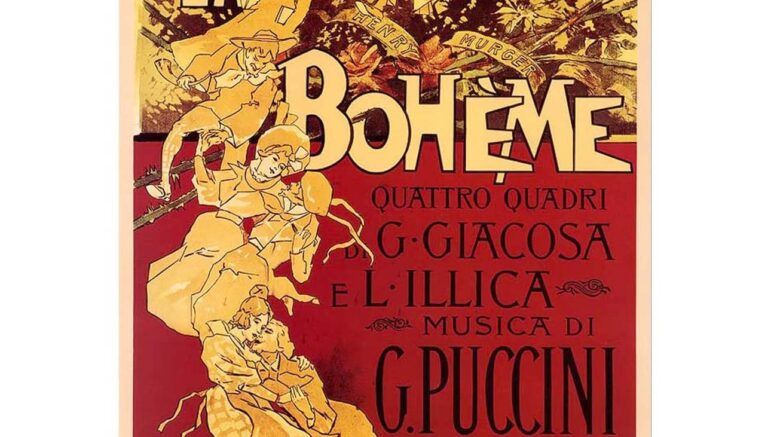

Puccini worked with two librettists to transform Murger’s novel into the opera’s libretto: Giuseppe Giacosa and Luigi Illica. It took 2 years of arguing, disagreements, pleading, controlling, and wrangling with his two librettists before he began setting the libretto to music. Puccini was incredibly demanding. Throughout his career Puccini was obsessed with the dramatic pacing of each scene and each act. He repeatedly sent scenes of the opera back to the librettists to revise and shorten. His publisher, Giulio Ricordi, who was also a composer, assisted in the process, coordinated the communication between the 3 and sometimes refereed their arguments. It was very stressful working with Puccini, who often changed his mind. And after 6 months of working on the libretto, Giacosa resigned from the project though Ricordi was able to persuade him to continue. But 21 months later Giacosa had had enough of the constant pressure and dissatisfaction from Puccini and wrote to Ricordi: “I swear to you that I can’t go on revising everything 20 times. I’m tired to death of this constant remaking, retouching, adding, correcting, cutting, piecing together, extending on the one hand and reducing on the other. I have written this damn libretto from beginning to end three times and certain sections 4 and 5 times. I am sick to death. Curse the libretto! How am I supposed to finish at that rate? I swear to you they’ll never trap me into doing librettos again! Tomorrow I’m installing myself all alone in some quiet hotel. And there, I will have finished in a few days. But will it be finished then? Or will we have to start all over from the beginning?”

Once Puccini had finally approved the libretto, it took him less than a year to write the music for La Bohème. Most of it was composed at his home in Torre del Lago, where Puccini had befriended a small group of painters with whom he formed the Bohème Club, who met in an old hut to eat, drink and play cards.

The audience at the world premiere included royalty, noble families, and several important composers including Mascagni. One local critic wrote: “Bohème failure. It won’t make the rounds.” Others wrote that they didn’t think the opera would become a popular favorite. Another wrote “La Bohème will leave no large imprint on the history of our lyric stage, and it will be well if the composer will persuade himself that this has been a brief detour in the road of art.” Or this review: “You have today conceived the whim of forcing the public to applaud you where and when you will. For the future, turn back to the great and difficult battles of art.” Another critic wrote: “We ask ourselves what has pushed Puccini along this deplorable road of Bohème.” And another: “Let us await better things from the strong endowment of this composer.” Another could not forgive Puccini “for composing his music hurriedly. It is music which can delight but rarely move. Even the finale of the opera seems to me deficient in musical form and color. God forgive him!” Then there was this one: “The music of La Bohème is real music, made for immediate pleasure, intuitive music. And that is precisely for this reason that we must praise and condemn it.” And finally: “On the whole, melodic invention is extremely scanty.” Toscanini himself wrote: “Puccini took it very badly; and left him like a rag.”

In the end it is always the judgment of the public that counts. At its conclusion the audience jumped to its feet with great enthusiasm. Throughout the evening they called Puccini out on stage a total of 15 times. In fact, in the weeks following the world premiere in Turin, La Bohème was so popular that it was performed there 24 times, and each performance sold-out!

It was then performed in Rome, Trent, Brescia, Bologna, Naples, and Milan’s La Scala. In Florence, Puccini was called on to take some 40 curtain calls! Queen Margarita attended the second performance in Rome and Puccini was nominated Commander of the Italian Kingdom. The Sicilians loved it so much at its first performance in Palermo that at its conclusion they continued applauding, bringing Puccini onstage for 45 curtain calls, prolonging the performance until one in the morning. And when the audience refused to leave, the last scene had to be repeated, even though some of the orchestra had already left and the singers had changed into their street clothes!

It quickly began to be performed internationally: in Alexandria, Moscow, St. Petersburg, Helsinki, Algiers, Lisbon, Manchester, Glasgow, Edinburgh, Rio de Janeiro, Mexico, The Hague, Prague, Barcelona, Athens, Chile, Malta, Warsaw, Zagreb, Helsinki, Budapest, Berlin, Munich, Paris, Brussels, Los Angeles, New York, Vienna, where it was conducted by Gustav Mahler, and in Buenos Aires where it was conducted by Toscanini. It has become one of the most popular and often performed operas. Debussy said: “If one did not keep a grip on oneself one would be swept away by the sheer verve of the music. I know of no one who has described the Paris of that time as well as Puccini in La Bohème.”