Fiddler on the Roof is based on Tevye the Dairyman and other stories by Sholem Aleichem. It’s about a Jewish community in 1905 in the fictitiously named village of Anatevka, Ukraine. He wrote the stories in Yiddish between 1894 and 1914 and they are based on Aleichem’s own upbringing.

The plot centers on Tevye, a poor Jewish milkman and his wife, Golde, whose 3 eldest daughters flout their community’s tradition of arranged marriages by choosing their own husbands. According to Tevye, the lives of the Jewish residents of Anatevka are as precarious as a fiddler on the roof, and by the end of the film are forced to leave the village by order of the Tsar.

The original stage version opened in 1964. It was the first musical in history to have a continuous run of more than 3,000 performances, and held the record for the longest running Broadway musical for almost 10 years. It won 19 Tony awards, and led to five Broadway revivals, and an incredibly successful film adaptation. It was also the longest running musical ever produced in Tokyo.

The script was written by Joe Stein, and the music was composed by Jerry Bock, with lyrics by Sheldon Harnick. Its producer, Harold Prince, chose Jerome Robbins to choreograph and direct the show. The lead character, Tevye was played by Zero Mostel.

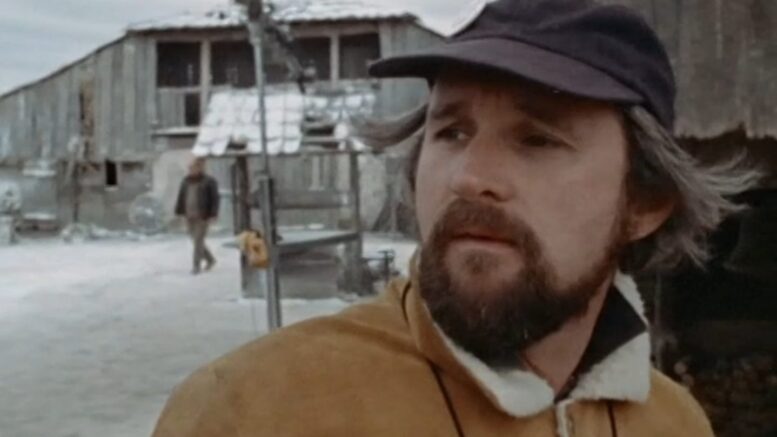

Fiddler was made into a movie in 1971, produced and directed by Norman Jewison. It starred the 32-year-old Israeli singer and actor, Chaim Topol. The music was arranged, orchestrated, and conducted by John Williams.

The interiors were shot in London, and Norman Jewison chose the former Yugoslavia to shoot the exterior scenes, which he felt closely resembled the story’s setting in the little Ukrainian village or as it’s referred to in Yiddish, the shtetl.

A documentary about the making of the film entitled Fiddler’s Journey to the Big Screen was created in 2021, produced and directed by Daniel Raim. And in 2020 Sheldon Harnick’s nephew, Aaron Harnick announced that he was co-producing a remake of the film.

Fiddler on the Roof received eight Academy award nominations, including Norman Jewison for best picture and best director, and Chaim Topol for best actor. It won a Golden Globe Award for best musical or comedy motion picture and Chaim Topol won a Golden Globe award for best actor. It was the highest grossing film of 1971, and is often considered to be one of the greatest musical films of all time.

Norman Jewison’s Solidarity with the Jewish People

“No Jews, Nigg****, or Dogs.”

The sign was posted at Kew Beach, a five-minute walk from Norman Jewison’s childhood home in the Beach district of Toronto. He passed it countless times during his childhood, on summer days spent swimming and canoeing in Lake Ontario, among families whose day at the beach was not to be spoiled by the sight of a Black person or a Jew. He had seen similar signs barring Jews from the nearby Balmy Beach Canoe Club. They were a feature of the social environment into which he had been born in 1926.

If you want to understand Norman Jewison, start with his name. Jewison: son of a Jew. The fact that he was actually the son of two Anglo Protestants didn’t count for much on the streets of Toronto in the 1930s. Antisemitism was woven into the social fabric of a city in which Jews were banned from hotels and beaches and blocked from entering the professions. And Toronto’s antisemitism was a physical reality for a boy named Jewison in the 1930s.

Norman remembers being attacked by local ruffians who called him “Jewy” and “Jew-boy” from the age of three or four. He befriended Jewish kids in the neighborhood— and there was safety in numbers, although they were still beaten up from time to time.

Toronto of the 1930s was not what you could call a safe space for Jews. One summer night, three weeks after Jewison’s seventh birthday, members of what the papers called the “swastika movement” descended upon a baseball game at Willowvale Park (now Christie Pits). The Toronto Star described a gang “openly flourishing pieces of metal pipe, chains, wired broom handles, and even rockers from chairs.” Cries of “Heil Hitler!” pierced the air. As many as 10,000 Torontonians eventually joined the melee. “Heads were opened, eyes blackened and bodies thumped and battered as literally dozens of persons, young and old, many of them non-combatant spectators, were injured more or less seriously by a variety of ugly weapons,” the Star reported. The following night, gang members began roaming the streets in search of Jews, where they surrounded a 22-year-old medical student named Louis Sugarman, “pummeling him with their fists and inflicting acute damage on his head with a heavy iron pipe.” Witnesses claimed that police efforts to pursue the perpetrators was lackadaisical. Reporters uncovered that “scores of Toronto constables today carry swastikas around on their keyrings” and that the emblem was stamped on locker keys at a police motorcycle depot.

“The whole thing of carrying this name that starts out with the letters J-E-W—it affected me deeply,” Jewison later said. Even as an adult, he couldn’t get into a Scarsdale golf club. “One thing that really sets me off is any kind of racial prejudice or intolerance,” he said. Jewison’s anti-racism was pounded into him by experience.

Jewison’s personal interest in Judaism deepened when he became the director of Fiddler on the Roof. In late September 1969, Jewison flew to Jerusalem and spent a few days embedded among descendants of the Eastern European Jews depicted in the Sholem Aleichem stories that were the basis of Fiddler on the Roof. He greeted the Sabbath with residents of Shaare Hesed and visited a synagogue for Simchat Torah. He shared the Sabbath meal with an Orthodox Jewish family, following the customs and traditions as they had been observed in the shtetl. He sang the Zemirot, the family songs of Sabbath. Saturday morning, he took a guided tour of Meah Shearim, the Hasidic Quarter, and attended prayer at the Western Wall with professor Davis.

The experience was unexpectedly moving. Jewison was touched by the strength of the familial bonds of the Orthodox Jews, their reverence for tradition, and what struck him as the clarity of their lives. He loved the theatricality of their traditions, their devotion to the details of its performance. Mistaken for a Jew his entire life, Jewison discovered a deeply felt connection with his Jewish hosts and their historical burden. “I spent quite a bit of time in Jerusalem,” Jewison said later. “It was quite possible for me to identify with Tevye, and with the Jewish religion. The more I studied it and the more I exposed myself to Jewish homes, more Orthodox homes… I identify with certain aspects of the Jewish religion. I find it a very personal religion.”

Jewison had been almost overwhelmed with emotion when, after the Jerusalem premiere of Fiddler, Prime Minister Golda Meir squeezed his hands in approval. “Your words that night meant more to me than all the Oscars or critical praise the film ever received,” Jewison later wrote to Meir.

Jewison wrote to his old friend Carl Reiner that in making Fiddler on the Roof he had “found, in a way, in myself my own Jewishness.” His time researching the film in Jerusalem had also awakened a love of Israel. Jewison penned an article for Variety encouraging more Hollywood producers to film in Israel. “There is a spirit in the country and among its people that grabs you,” he wrote, “and if you spend any time there you will never be the same.” Jewison’s profound identification with the Jewish people was unshakable.

In 2010, Norman Jewison married his second wife, Lynne St. David, beneath the chuppah in their garden. If the chuppah represents home and openness, its place in the ceremony also signified, in some small way, the influence that Jewish culture, history, and sensibility had always exerted over Norman Jewison’s imagination.

(Adapted from The Canadian Jewish News based on Norman Jewison: A Director’s Life by Ira Wells 2021.)

“Maybe Steve McQueen’s right. Maybe it all just gets down to power and juice; I don’t know. But I’ve never felt that I wanted power. The only thing I’ve ever felt, is I wanted something very definite to say about the programs I directed. I don’t think that’s asking too much. That’s what you’re hired to do. ‘Cause there’s no sense doing anything you’re not going to be happy with. There’s no sense in entering a relationship. When I become involved in something I go to bed with it. It’s my love. It means more to me than anything in the world. Anything. When I commit myself to something I want to commit my mind, and my body, and my spirit, and every ounce of energy and effort I have to make it successful, to make it work, to make it somehow materialize into something that’s beautiful, or good, or moving. And anyone who doesn’t feel that way I don’t want around me, and I don’t want them to be involved in it.”

(Norman Jewison, 1971)

Watch Norman Jewison on Fiddler on the Roof with prisoners’ family photos from Auschwitz: https://youtu.be/cB_PeMp3_tE

Watch Norman Jewison reading from Sholem Aleichem’s writings: https://youtu.be/T69mRIfJSRE