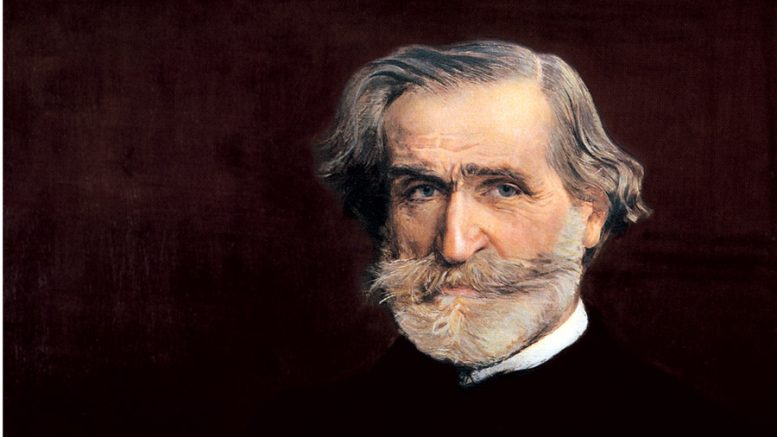

Giuseppe Verdi was born in Roncole in northern Italy in 1813. He composed 28 operas. While in his 20s Verdi experienced the death of his 1st wife and the deaths of his infant children. This threw him into a terrible depression. And he refused to continue composing, until he read the libretto of Nabucco. He was twenty-eight when he composed Nabucco. Its world premiere was at Milan’s La Scala opera house. In Verdi’s day, the country of Italy didn’t yet exist. The Italian peninsula was divided into 10 political units consisting of 2 kingdoms, 3 republics, 4 duchies and a theocracy known as the Vatican. Most of these were dominated by the Austrian Empire.

Nabucco broke all box office records at La Scala up until that time. And it was not long before Verdi became a symbol of the Risorgimento, the movement for Italian unification. The Buddhist philosopher, Daisaku Ikeda wrote: “The cries for liberty it inspired in the Italian people spread from heart to heart like wildfire… Filled with pride, they all began singing Verdi’s melodies. After Nabucco Verdi produced a succession of operas to inspire and encourage the people. He composed always and solely for the people. That is where his greatness lies.”

Nabucco is based on a story from the bible. The Jews were taken as prisoners, and led by chains to the foreign land of Babylon. In the famous Chorus of the Hebrew Slaves from Nabucco this scene shows the Jews in captivity in Babylon resting after a long day of forced labor. They lament their unhappy fate as prisoners, singing: Va, pensiero, sull’ali dorate… Go, thought, on golden wings… The thought is of their beloved homeland. They sing: “Oh, my country so beautiful and lost!” They yearn for their homeland. To Verdi, the suffering of the biblical Jews was similar to the anguish of the Italians under foreign domination. It is the struggle of an oppressed people for freedom. Dr. Ikeda wrote: “It was as if the Italian people’s own subjugation by another country was mirrored back to them. The opera provided ‘wings of hope’ upon which the hearts of those who aspired for Italy’s freedom could majestically soar.”

Verdi’s next opera, I Lombardi created a frenzy. It’s about the Lombards on a crusade to the Holy Land. The tenor sings: ‘The Holy Land today will be ours’, to which the chorus and the audience replied, ‘Yes! War! War!’ Pandemonium broke out in the theatres. The choruses from I Lombardi and Nabucco became popular hymns of the revolt in Lombardy and are still taught as patriotic anthems in the elementary schools of northern Italy. Even today Va Pensiero is thought of as Italy’s second national anthem. At most performances, the audiences demanded that it be repeated, despite police prohibitions against encores!

In his opera Attila, which is about Attila the Hun, the audiences were electrified by the line ‘You may have the universe, but leave Italy to me’ This quickly became an anti Austrian slogan.

His opera La Battaglia di Legnano is about the battle of Legnano, when Italian cities united to defeat the German invader, Frederick Barbarossa in 1176. It was the first Italian victory over a German emperor. Its world premiere took place in Rome. When Verdi was in Rome for the rehearsals, crowds gathered around him whenever he was spotted on the street. At the dress rehearsal a crowd of people broke into the theatre, packing it full, and called Verdi to the stage 20 times.

It was illegal for people to gather publically, but going to the opera offered them a way to defy the authorities. Opera was the main form of entertainment. The house lights were kept on, because during performances, the audience would leave their boxes to socialize with each other.

These patriotic operas were a weapon against the occupying forces. At the world premiere of La Battaglia di Legnano, pandemonium broke out when the audience heard the opening chorus: “Long live Italy! A sacred pact unites all its children!” The audience became delirious and came close to starting a riot. La Battaglia di Legnano became so popular that at every performance the entire 4th act had to be repeated. The pope had fled the city and 10 days later the Roman republic was established. However this didn’t last very long, and Verdi expressed his frustration to a close friend: “Let us not talk about Rome!! What good would it do? Force still rules the world! And Justice? What can Justice accomplish against bayonets? We can only weep over our misfortunes and curse those who are responsible for so many disasters…I have an inferno in my heart.”

Verdi himself stage directed his operas, demonstrating to the singers how to stand, fall, embrace and address each other throughout a 4-6 week period. He rehearsed the singers and the orchestra and conducted the first three performances of almost all of his 28 operas. He was described at rehearsals: “shouting like a mad man, stamping his feet so much that he looked like he was playing the organ, while sweating profusely. He is music from head to foot, fighting for his own ideals, pouring his artistic genius into those men, those women, searing them with his own flame, which burns him, too; running upstage, and stopping the choristers to correct something.”

During these early years, Verdi composed an average of 2 operas per year composing from early morning until midnight, usually with one break! His favorite drink was very strong coffee. Verdi referred to this period in his life as his “years of slavery.” As early as age 31 he announced his decision to retire. And when he was 46, he announced that he was definitely retired. In fact this is how he signed one letter “A deputy of central Italy who was stupid enough to write music for many years. G. Verdi” He also wrote: “I cannot wait for these next three years to pass. I have to write six operas, then addio to everything.”

But within 2 ½ years the Imperial Theatre in St. Petersburg, Russia commissioned him to write a new opera and he began composing La Forza del Destino, The Force of Destiny. Verdi was a great symphonist. The Preludes and overtures to his operas are phenomenal.

Italians began to use Verdi’s name as a political slogan, which expressed their secret support for a new potential king: Vittorio Emanuele.

Vittorio Emanuele King of Italy (in Italian): Vittorio Emanuele Re D’ Italia (abbreviated): V. E. R. D. I.

“VIVA VERDI!” (literally): Long Live Vittorio Emanuele King of Italy! “Viva Verdi!” was scratched on walls and shouted in the streets. Verdi became a member of Italy’s first Parliament.

Back to Nabucco! The soprano who sang the world premiere of Nabucco was Giuseppina Strepponi. Before meeting Verdi she had had 3 or 4 illegitimate children from different men. They were given to foster homes, and her “reputation” in the opera world was well known. She and Verdi soon became lovers and lived together for 16 years before marrying. She was 2 years younger than him. They both suffered on and off from depression, and the relationship had its ups and downs. From her diaries, we learn that at times Verdi became very angry with her and with their servants, and was unable to control his bad temper.

When he was 59 Verdi began an affair with Teresa Stolz, who was the soprano in many of his operas. She was 21 years younger than Verdi. His wife insisted that he end the affair, but Verdi threatened to kill himself. His wife actually befriended the younger woman, and suffered through the affair for years. Nevertheless, Verdi and his wife spent 54 years together and he outlived her by 3 years. Verdi living with Giuseppina Strepponi in the small town of Busetto, caused quite a scandal, and they were terribly mistreated. To get away from everyone, Verdi purchased a home in the country outside the village of St. Agata. When he was 38, Verdi legally separated himself from his parents. His mother died six months later. That same year, Verdi and Giuseppina moved into their new home, and he gradually built it into a grand country estate surrounded by acres of plants and trees. Verdi employed up to 10 house servants and 18 gardeners, even in the winter! As a landlord he sometimes greatly reduced the rent payments, or did not collect them. He also purchased and operated several farms and employed 200 farm laborers whom he personally supervised! He even supervised the construction of a complex irrigation system for his gardens and fields. Verdi’s wife wrote that “His love for the country has become a mania, madness, rage, fury, everything exaggerated. He gets up almost at dawn, to go look at the wheat, the corn, the grapevines, etc. He comes back dropping with fatigue.” He soon had an abundance of farm animals, and loved the physical labor of gardening, and tramping about in the fields. He marked his career by planting selected trees: a sycamore tree for Rigoletto, an oak for Il Trovatore, and a weeping willow for La Traviata!

Verdi sold his operas to his publisher, who then leased the operas to various theatres for each performance, and paid Verdi a percentage of these rental fees. For 25 years Verdi prohibited the performances of his operas at La Scala because he found the standard of performances there to be unacceptable. In fact, he had a clause in his contracts that gave him the right to decide which theatres would be allowed to present his operas. In this letter to a close friend, he complains about the theatre in Naples during rehearsals for Aida. “I knew how disorganized this theatre was, but neither I nor anyone else could have imagined it to be like this. The ignorance, the inertia, the apathy, the disorder, the indifference of everyone to everything, is indescribable, and unbelievable. If I hadn’t been such an imbecile as to give my word…I would have gone off even in the middle of the night, to dig my fields and completely forget about music and theatres.” He also frequently complained about the Paris Opera Theatre. He wrote to his French publisher that a performance must have “fire, spirit, muscle, enthusiasm; all these are lacking at the Operà.” And he hated when singers or conductors changed his music. His contracts included a clause that called for the publisher to pay him a huge penalty fee if theatres performed his music with cuts, transpositions, or other changes.

In another letter he wrote: “I never succeed in producing those sweet words, those phrases that send everybody into raptures. No, I shall never, for instance, know how to say to a singer, ‘What talent! What expression! It couldn’t have been sung better! What a divine voice! What a baritone, there never has been anything like it for fifty years…What a chorus! What an orchestra!…Time and time again I have heard them say in Milan… ‘La Scala is the world’s leading theatre’. In Naples, ‘The San Carlo is the world’s leading theatre’. In St. Petersburg, ‘the world’s leading theatre’. In Vienna, ‘the world’s leading theatre’ (but in their case, it’s true). In Paris they think the Opéra is the leading theatre of two or three worlds. And I end by saying that one second-leading theatre would be better than all these ‘leading’ ones.”

To the father of a young playwright he wrote: “…He should imitate no one…Let him put his hand on his heart, and listen to it. He shouldn’t become conceited by praise nor depressed by criticism. He should not fear the darkness that surrounds him. Let him go straight on, and if sometimes, he stumbles and falls, he must get up, and go straight on.”

Once a libretto was completed, Verdi memorized it, and then developed his musical ideas slowly, walking around his farm brooding on it until the concept of the whole fell into place. Then he would quickly write it all down in the heat of inspiration. It didn’t take Verdi long to orchestrate his operas. The music came to him in a complete package, both the vocal and orchestral parts. He said: “The thought presents itself whole…The difficulty is always in writing it down fast enough to express the musical thought in its entirety, precisely as it came into my mind.”

As a child Verdi had been an altar boy. One day at church when he was 7, he became distracted by the music and wasn’t paying attention to the priest’s instructions. The priest pushed Verdi, and he fell. Humiliated, the young boy cursed the priest, saying: “May god strike you with lightning!” Eight years later, the priest was struck by lightning and killed. In his old age, Verdi’s advice to a young relative was: “Sta lontan dai pret!” Stay far away from priests!

In a letter to his friend, Countess Maffei he wrote: “I don’t raise my hat to counts, marquesses, or to anyone.”

Verdi was opposed to the catholic church’s financial and political power, and the priesthood’s abuse of its power. In 1864 the pope issued a document called the Syllabus of Errors in which he listed what he called the 80 “errors of our time”. These included freedom of conscience, religious toleration, freedom of discussion, and freedom of the press. It was a reactionary attack on everything that was progressive in the 19th century. And three years later the pope proclaimed the dogma of the “infallibility of the pope”. This quickly led to the final step in the independence and unification of Italy. It was around this time that Verdi, greatly disturbed by the church’s opposition to Italian unification, composed a 5 hour long opera about the conflict between church and state. Verdi’s Don Carlos is based on Schiller’s play Don Carlos, which takes place during the Spanish Inquisition. Verdi depicts on stage, the tragic burning at the stake of so-called heretics by the church. These unfortunate people were often innocent.

There is a scene between King Philip II of Spain and the Grand Inquisitor, who was given power by the pope to decide the fate of these unfortunate people: who would be burned and murdered? Verdi describes this man as being 90 years old and blind. He’s a symbol of the forceful negativity of the church. The Grand Inquisitor is someone who just plows through, unseeing, and uncaring for the idealism of youth, insisting on tradition. Verdi’s musical characterization of him is incredible. You feel the tremendous weight of the church. After the king’s son, Don Carlos, threatened to stab his father, the king has him arrested, and asks the GI what he thinks about having his own son murdered. This is so shocking. Yet, the Grand Inquisitor gives him justification saying: “god sacrificed his only son.”

Verdi’s wife commented on his anticlergy attitude and refusal to believe in god or any higher power. “I won’t say he is an ‘atheist’, but certainly a very doubtful believer.” When Countess Maffei’s lover died, he wrote her a month later: “There are no words that can bring comfort during this kind of misfortune…Something else is needed. You will find comfort only in the strength of your soul and in the firmness of your mind.”

Verdi’s gods were Dante and Shakespeare, and his saint was Manzoni, whose novel I promessi sposi was a milestone in unifying the Italian language and a symbol of the Risorgimento. His enemies were hypocrisy, mediocrity, pretentiousness, and the priests.

He wrote to his protégé, Emanuele Muzio: “Respect yourself and make others respect you: never a moment of weakness: treat men of the highest rank just as you treat those of the lowest: don’t favor anyone; don’t have likes and dislikes; and don’t be afraid to swear occasionally.”

During the wars of Italian independence, Verdi launched an appeal for contributions “to help the wounded and the poor families of those who died for our country.” And in the spring of 1879, when the Po river flooded the provinces of Piacenza, Parma, Mantua and Ferrara, Verdi wrote: “This winter there will be famine and people dying of hunger…At the same time the government is thinking of raising taxes…It really is a slap in the face.” Verdi organized a relief concert for the flood victims at La Scala where he conducted his Requiem.

Because there was no hospital near Verdi’s estate, he decided to buy a parcel of land, and personally financed the construction of a hospital for his 200 farm laborers and their families. The mayor wanted to name it after Verdi, but he refused, and insisted that the only word inscribed on the façade should be “Hospital” Ospedale. After his death his name was added to the building’s facade. Verdi personally supervised the construction and paid the workers himself every Saturday.

Verdi kept two copies of Shakespeare’s works next to his bed, and created 3 operas from Shakespeare’s plays: Macbeth, Otello, and Falstaff, which is based on the Merry Wives of Windsor and Henry IV. He also wanted to write operas based on Hamlet, Romeo and Juliet, and King Lear, but never did.

When he was 74, Verdi decided to compose Otello with Arrigo Boito as librettist. After Boito completed the libretto, Verdi began composing Otello, but then stopped. His wife, his publisher, and the director of La Scala, all tried to get him to continue. But Verdi was completely engrossed in farming and wrote that he was “surrounded by cows, oxen, horses, working like a peasant, bricklayer, carpenter…master stonemason, and blacksmith” repairing many of the tenant houses and building new ones. He wrote that he had “said goodbye to books and music” And he completely forgot about composing Otello! His protégé, Muzio, told him that he ought to finish the opera, and that it was a great way to cover the expense of the hospital he wanted to build, and even of providing it with an endowment. That’s what got him to continue composing Otello! Verdi wrote: “When I am alone and am wrestling with my notes, then my heart pounds, tears stream from my eyes, and the emotions and joys are beyond description.”

One of his conditions for the world premiere of Otello at La Scala was that the poster advertising Otello would not indicate the date of the first performance! He had the right to cancel it even after the dress rehearsal, if he was not pleased with the rehearsals. And if anyone attempted to produce the opera, his publisher would have to pay him a fine of 100,000 lire!

When rehearsing with one of his singers he said: “I’ll never stop urging you to study closely the dramatic situation and the words; the music will come by itself. In a word, I would be happier if you served the poet rather than the composer…Keep the dramatic situation well in mind.”

During his lifetime, it was said that Verdi had begun imitating Wagner, a remark that he hated, and denied. He did admire Wagner’s music, however, and had this to say about Tristan und Isolde: “I still cannot quite comprehend that that it was conceived and written by a human being. I consider the second act to be one of the finest creations that ever issued from a human mind. This second act is wonderful, wonderful…quite wonderful!”

Verdi’s opera, Aida, was written for a commission from Egypt and had its premiere in Cairo. It was the first opera Toscanini ever conducted, in 1886. He knew Verdi personally, and received the composer’s praise for his interpretation of his music.

At the end of his life Verdi bought a piece of land in Milan and financed the construction of a Rest Home for Old Musicians. Its capacity is for 100 residents. He wanted to provide a place where professional instrumentalists and singers would be able to live out their sunset years with great dignity. After composing 28 operas and other compositions, he said that his most beautiful work was the Rest Home.

Verdi died in 1901, at the age of 87. One month before his death, he arranged for all of his compositions from his youth to be burned!

At his death Verdi’s net worth was approximately 35 million dollars. In his will, he left money to day care centers, the childrens’ rickets hospitals, and the hospitals for the deaf, mute, and blind of Genoa. He left money to each of his servants. He left 9 farms to his hospital, and stipulated that part of the income from these farms was to go to the nursery school in Cortemaggiore. The hospital was also to give money to 100 poor people in Villanova each year, and each year give money to 50 poor people in Roncole, the town of his birth. To the Rest Home he left money, stocks, bonds, and his author’s rights and global royalties from all his operas.

As a result, I am delighted to say that over 100 years later, these two institutions are still functioning.

The will also included his strong wish to be buried with his wife in the chapel of the Rest Home.

Several weeks after his death, a quarter of a million people lined the black-draped streets of Milan as his coffin was transferred from the cemetery to the Verdi Rest Home.

Daisaku Ikeda wrote: “In later years, he is said to have remarked, ‘I am nothing but a peasant.’ And it was with this recognition of being from humble origins that, as a friend of the people, Verdi devoted his life to composing operas out of his love for music and his love for Italy.”

View short video: https://youtu.be/qRcmRuADyUA